Fall observations

October 1

This past weekend I visited a working farm in Gap where the owner produces herbs and fresh vegetables for Philadelphia restaurants. He had 10 quince trees growing in two rows on his property which he was observing. He said that each one was a different variety, and in another year or two it would become apparent to him which was the best producer. At that time, he would eliminate the trees that didn't live up to his expectations and just keep one. I mention this because I had thought briefly about having a quince tree on my small property. However, after seeing how they grow at the Barnes and how unattractive they are, I decided against it. His two rows of quince were very attractive, so perhaps I'll ask him in the future for the name of his successful tree and add it.

Our class took a field trip to the private home of talented gardener who had been working on her garden for 38 years. It was a joy to see how she has transformed the grounds from deep woods into aesthetic planting beds. When I saw how she severely pruned the Rose of Sharon and turned them into rose-like standards, I was impressed. She said that the severe pruning cuts down on their self sowing. The other outstanding tree was her Japanese red maple that had also been pruned into a horizontal form. There is a Japanese maple on my property, and I have asked to have it pruned in a similar fashion. The arborist reminded me that it would take several years for it to acquire the form that hers has. Gardeners must be patient.

I have become aware that plant nerds snicker at the mention of the glorious rose which is seen all over the city, the Knock-out. Each time I have come to Philadelphia in the summer, I have been taken by the beauty of the rose. It is care-free, and seems to thrive on neglect. The only negative I can find in it is that it is everywhere. What is not to like in a rose that needs no attention, and that thrives in places where weeds were growing before?

Another revelation to me in Philadelphia is how strong the gardening culture is. Correct me if I am wrong, but it seems that there are a lot of knowledgeable female gardeners who maintain other people's gardens. They provide design work, suggest the plants, purchase and plant them, weed the beds, deadhead, and whack them back when the time comes. The male yard crew comes through with their noisy gasoline motors and cut the grass and edge the paths. This is unlike gardening in Miami. There most houses have a front and a back yard. Most people still value their green lawn. They might plant a palm tree or two and put in a few impatiens, and call it a garden. I am not aware of a gardening culture that hires others to come in and do the creative work of pulling a garden together and maintaining it throughout the season. When they hire help, it is to cut the grass and maintain the pool.

Mulch: In Miami, I had one or two dump-truck loads of woodchips dropped on my property every year. My yardman would spread the woodchips in all the beds. My intention was to cut down on weeds, hold the water in the soil, improve the soil, and keep plants cool in our heat. As soon as I moved to Philadelphia, I started noticing black mulch. My first thought was that it must come from a black-trunked tree. In my opinion, it was unsightly. On our last class fieldtrip, one of the classmates commented on the dyed mulch, and that cleared up the mystery for me. In Miami, the mulch that is sold in big box stores is dyed red. I find it unsightly, too.

Our class made a fieldtrip to a native plant nursery this week. The nursery observes the plants growing for a period of several years before they make a decision on its worthiness to be propagated and released to the public. These trials help gardeners know that what they are planting in their gardens will be true and sturdy in the years to come. I have been interested in green roofs for several years, but had never seen one. There was a small green roof at the nursery which was covered with a variety of sedums and other succulents. I asked the guide whether the plants could get through the winter months, and she assured me that they would. Since my crew will soon be exposing the boulder wall on my property, I will be looking for plants to tuck into the pockets of soil. There is such a variety of sedums to choose from.

October 15

October 15: Since I have recently moved to the Northeast, I observe that the seasons change very quickly here as compared to our two seasons in the sub-tropics (Miami). Gardeners are rushing to get their plants in the ground in time for the coming winter nap. Pruning limbs of dead tree branches needs to be done now. In Miami, we tried to prune our trees before the hurricane season started in order to avoid providing missiles for the hurricanes to send flying and damaging property. Bulbs need to be set into their spaces in the ground for a spring show.

My landscape crew installed the hedge between me and my backyard neighbors last week. It is a barrier that will become more and more beautiful as the years progress and as the trees fill out.

I mentioned in a previous posting that my property is L-shaped. Yesterday I met a new neighbor behind my house whose property abuts mine. She has lived in her house for over 20 years, and told me that the issue with my property is that all the neighbors whose land abuts mine have wanted to buy the parcel where I plan to have raised beds. I believe that the message my new hedge sends to any potential buyers is that the land is not for sale, and that I have taken possession of it (or am in the process of doing so).

I continue to think about the beautiful private garden our class visited last month on a field trip where the owner has gardened for 38 years. She has clearly spent a lot of time, effort, and money to convert her grounds into a beautiful space. I wonder who will buy this property when the time comes to sell it, and whether her work will be appreciated or whether it will be a deterrent to a future buyer. Will her investment in the grounds be returned at a higher selling price, or will the grounds and the care they require be a drawback to future buyers?

The reason this comes to mind is that I recently sold my property in Miami. I had gardened it intensively, starting with a pittosporum hedge that surrounded the property. There was a gorgeous cactus bed inspired by a recent trip to Arizona; raised beds in the back for winter vegetables, a small pineapple plantation in the front yard (about 50 plants), lighted pathways, native plants, laurel, allspice and edible palms, etc. I know the real estate markets are different between Miami and Philadelphia. My house received three full-price offers as soon as it went on the market, and part of the explanation for me was that people were charmed by the garden. As soon as the ink had dried on the contract, the buyers came in and chopped everything down. They removed the raised beds; tore out the mature hedge; got rid of the cactus bed. They planted grass everywhere. Just remembering this makes me sad. It was their property and they could do with it as they pleased. The experience makes me question whether indulging in a garden is an investment or an expensive hobby.

One of the best parts of the horticulture program at the Barnes is the fieldtrips we make as a class to see gardens and nurseries which we wouldn't normally be able to access. We learn so much by observing best practices that others implement. For instance, the trials at the native plant nursery last 3 years before a plant can go into production. How many plants "failed the test" and never made it to that stage? I feel that all agriculture is an experiment, and I believe that three years is enough time to allow a plant to make it on my property before removing it forever. This year I will be planting a fig and a mulberry tree. If they survive the winter and start producing fruit within the three-year period, I will keep them. If not, I will replace them with another experiment.

This past Monday when we had classes at the Barnes, I skipped my last class when we were supposed to walk the grounds of the arboretum to identify trees. The weather turned colder than the weather forecast had predicted, and it started drizzling. I hadn't worn or brought the right clothes for walking outdoors and decided that instead of getting chilled to the bones, I would go home and order new winter clothes to help me get through the winter. My plan is to leave an extra jacket and rain gear and boots in my car so that I won't get caught unprepared again. I feel guilty about missing a class, but I didn't want to be sick for the rest of the week.

November 1, 2014

The temperature is gradually dropping as we ease into the winter. Twice in the past week there were ice crystals on my windshield. It forced me to spend a few extra minutes melting it before there was enough visibility to drive safely. I wonder how the plants are coping with the cold.

My landscape crew is largely missing in action. When we began the landscaping project on October 1, I wrote to a friend that it should be finished within the week. Wrong! The crew planted the privacy hedge and pulled out most of the grass from my ridge. The ridge was then sparsely planted with prostrate junipers, sedums, and black-eyed Susans. They plan to mulch it heavily to hold the soil. Still pending, and of great interest to me, are the raised vegetable beds at the back end of my property, and the split rail fence at the front. There are still blueberries, a fig, and a mulberry tree to plant. The teachers at the Barnes keep saying that it's too late to plant certain things. Will these plants come through the winter, or will I have to replant in the spring?

The composter is finally in place and I can start filling it. I hope that our professor of soils at the Barnes will deal with composting soon.

A groundhog has a burrow under the shed. This week I bought a battery operated spike that gets buried in the ground. Every 30 seconds it emits a beep which is said to discourage the ground hogs from staying here. My brother in Virginia says they will soon go into hibernation, so my spike may be useless in the winter. I must remember to change the batteries in the spring. Question: if the beep irritates groundhogs to the extent that they abandon this location, does the same beeping irritate other ground creatures and organisms?

I had my shed painted from the typical "barn red" to a deep, nearly black green. Every time I looked out my window, the shed aggressively assaulted my eyes, so I toned it down. It has become nearly invisible with the new paint.

Our class has made three very interesting field trips. One was to the home of a woman who has gardened there for nearly 50 years. She showed us a photo the lay of the land when she and her husband bought the property. It was a house with a dauntingly steep hill located in the backyard. She gradually converted the slope into a terraced vertical garden with paths, irrigation, and lighting. The trees have matured, and she installed whimsical sculptures throughout. She was falsely apologetic for the property, saying that it was all that she and her husband could afford at the time. I think that sometimes our hardships are blessings in disguise. What would she have done with the boring vista of a flat surface to garden on?

Another private garden that we visited belongs to a man who is a specialist in camellias. His two-acre spread is intensely gardened into rooms. His blessing in disguise was a 200-year old oak which fell in his backyard. Once removed, his yard suddenly had lots of sunlight which changed the kinds of plants that could grow in the space. I was interested in seeing how he had built a large cage to surround the blueberry bushes in his vegetable garden to protect the ripening fruit from hungry birds. I must do the same with my new blueberry bushes. I also observed cages that he had made to protect his bulbs from squirrels. The cages were made out of chicken wire and upside-down bicycle baskets.

The third garden was Chanticleer, an enchanting public garden which closes during the winter months. What I admire about this garden is how its team of gardeners clearly use their imagination to create garden displays that interest children and adults alike. From the ruins to the vegetable garden to the quirky furniture and decorative items installed in the beds, it is a delight to behold. I enjoy the combination of bright colors of flowers in the perennial beds, and hope that I, too, can have a perennial garden in the future.

Regarding the homes that we have visited with their spectacular gardens, I continue to wonder what is going to happen to them when the time comes to sell. The camellia gardener said that he planned to give his nephew the property. That's very generous, but is the nephew inclined to want to keep up the garden?

When I look at the few photos I have taken at various locations, what jumps out at me are the number of shots of succulents in all their wonderful combinations. Will succulents get through the harsh winter if I leave them outside? I know that the Opuntia cactus survives, so perhaps I can assume that succulents will, too.

|

November 22: This week I had the good fortune to be able to visit an

arboretum located on Martha's Vineyard.

It consists of 20 acres under cultivation and an additional 40 acres of

native woodland. This highly curated

collection of trees includes dogwoods, stewartias, rhododendrums and azaleas,

hollies, and other plants that are particularly suited to the harsh growing

conditions of the Vineyard. I had read

that the Polly Hill Arboretum had a collection of 70 Stewartias, and I am

certain that I must have seen most of them during my visit. In addition to the Stewartias, I also enjoyed

the dogwoods in the dogwood allee. Unlike

some large arboretum, the Polly Hill Arboretum is manageable in size. It is easy to stroll the grounds in an hour. Above are some of the photos I took of

Stewartias.

I've just finished reading the most fascinating book about the Lewis and Clark expedition to explore the American continent for expansion westward. Undaunted Courage, by Stephen E. Ambrose was on our reading list of recommended titles. What a miserable few years the explorers spent trying to find the passage to the Northwest,and what opportunities they had to witness the continent before settlers moved in. |

Backyard Dogwood: Cornus

I recall

growing up nearly six decades ago in north Florida in horticultural zone

9. As a child, my family would drive the

wood-paneled station wagon on the old two-lane highway, route 17-92 from

Daytona Beach to Sanford nearly 45 miles away,

to visit my grandmother for the day. My mother would have packed a lunch for my

three siblings, my father and me to eat when we arrived nearly an hour

later. The highway, such as it was,

went through woods of tall pine and bald cypress. At nearly sea level, some parts were swampy

and wet. I vividly remember my mother

pointing out the wild dogwoods that were blooming in the undergrowth of the

taller trees. How excited she was to see

them in their glory, especially as they were growing at the southern-most edge

of their continental distribution.

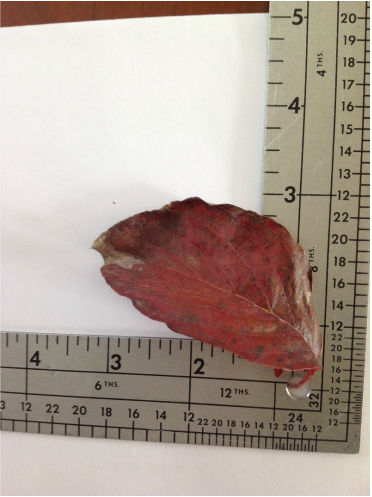

Four months ago, I bought a property in Philadelphia that has a dogwood tree on it. Judging from its size and the roughness of its bark, it is nearly mature. Whoever the far-sighted person was who planted it years ago made the typical mistake of a well-meaning gardener of locating it directly under the electric wires. It now grows into the wires and will always need to be pruned from time to time to provide clearance from wind storms. Nevertheless, I have been observing the tree from several vantage points from within my house. I saw it when I first arrived in August when it still had many green leaves on its branches. The squirrels visited daily to crack open and eat the approximately half-inch smooth red oval shaped fruits called drupes. An abandoned swing hung from a slender branch and moved lazily in the wind. Could that single branch support the weight of both the swing and a baby? Later, the nearly 3-inch long leaves turned red. Finally, like many other deciduous trees after the first frost, the leaves fell revealing the tree's structure.

I am left with questions about the tree on my property as I have not yet been able to observe it during a full year. What color will the flowers be? Pink? White? Is it the same dogwood that my mother so ecstatically identified years ago, probably a Cornus florida? The word "florida" means that it flowers, not that it's from Florida. I doubt that it is a Cornus kousa, the dogwood that many gardeners prefer because of its resistance to dogwood anthracnose disease and its superior hardiness to the wild growing trees. The bark of my tree is not mottled like the Kousa.

There are between 30 and 60 different species in the dogwood family. In order to identify a Cornus, one must consider not only the texture and color of the drupe (red, blue, or sometimes white) but also the shape, size and color of the flower. The apparent flower consists of four petals that are really bracts that surround an inconspicuous cluster of flowers. The bracts can be pink, rose, white or red. The bark is smooth when young and rougher with age. The leaves also play a role in the tree's proper identification. They are opposite and simple, elliptical, pointed and flat. The veins are noticeable. The sturdy wood has been used for tool handles, golf club heads, knitting needles, mallet heads and cutting boards.

Why do urban gardeners like the dogwood tree and use it in their landscaping? In small city lots, it is a compact tree that grows up to about 30 to 40 feet high and approximately the same width. It doesn't take up too much gardening space. When in flower, the trees are covered with beautiful blooms. It combines nicely with azaleas and rhododendrons and other like-minded acid-loving shrubs that bloom at the same time in the spring. Bees and butterflies pollinate the flowers. As an understory tree in nature, it prefers some shade, and it appreciates good drainage. It is so well liked that several states, including North Carolina, Virginia, and Missouri have named the dogwood as their state tree or state flower.

What are the pitfalls of caring for a dogwood? Aside from anthracnose disease, aphids can attack the tree. Powdery mildew can also be a problem. The tree cannot stand to live in arid conditions, so watering is required in times of drought. The tree is a larval food for a number of caterpillars. Some people don't care to see caterpillars feeding on the leaves. In some city lots, the soil is compressed, and the tree has a hard time establishing itself. Lawn care people are careless about the actions of their weed whackers, and they cut or bruise the bark, thus disturbing the vascular system. Some dogwood trees attract a borer which can lead to the death of trees. A flower and leaf blight (fungus Botrytis cinerea) can also cause unattractive wrinkled patches on the flowers and loss of blooms. The fungus is not usually a problem in dry conditions, however, and it can be controlled by a fungicide. The biggest natural stressors are exceptionally cold winters, dry, hot summers, and wet weather.

When I recall how excited my mother was when she spotted a flowering dogwood in the wild, I wonder now why she never planted one. We lived on four acres of partially wooded land, and she could have had many. She would never have transplanted a wild-growing dogwood onto her property, as doing so might have brought in diseased samples.

I am looking forward to the spring to see how my dogwood returns to life from its winter dormancy. I'll know that the tender new leaves will suddenly appear as if overnight. It will flower in April or May (I'm guessing). I'll watch to see which insects come to pollinate it. In early summer, I'll hang a newer swing on a branch knowing that it can support the weight of my growing grandchildren. I'll watch for the drupes to appear in the fall. The leaves will start to turn red in September. Then I'll know to expect that after the first frost in October or November the leaves will drop exposing the dormant trunk and branches. The cycle will start anew.

Four months ago, I bought a property in Philadelphia that has a dogwood tree on it. Judging from its size and the roughness of its bark, it is nearly mature. Whoever the far-sighted person was who planted it years ago made the typical mistake of a well-meaning gardener of locating it directly under the electric wires. It now grows into the wires and will always need to be pruned from time to time to provide clearance from wind storms. Nevertheless, I have been observing the tree from several vantage points from within my house. I saw it when I first arrived in August when it still had many green leaves on its branches. The squirrels visited daily to crack open and eat the approximately half-inch smooth red oval shaped fruits called drupes. An abandoned swing hung from a slender branch and moved lazily in the wind. Could that single branch support the weight of both the swing and a baby? Later, the nearly 3-inch long leaves turned red. Finally, like many other deciduous trees after the first frost, the leaves fell revealing the tree's structure.

I am left with questions about the tree on my property as I have not yet been able to observe it during a full year. What color will the flowers be? Pink? White? Is it the same dogwood that my mother so ecstatically identified years ago, probably a Cornus florida? The word "florida" means that it flowers, not that it's from Florida. I doubt that it is a Cornus kousa, the dogwood that many gardeners prefer because of its resistance to dogwood anthracnose disease and its superior hardiness to the wild growing trees. The bark of my tree is not mottled like the Kousa.

There are between 30 and 60 different species in the dogwood family. In order to identify a Cornus, one must consider not only the texture and color of the drupe (red, blue, or sometimes white) but also the shape, size and color of the flower. The apparent flower consists of four petals that are really bracts that surround an inconspicuous cluster of flowers. The bracts can be pink, rose, white or red. The bark is smooth when young and rougher with age. The leaves also play a role in the tree's proper identification. They are opposite and simple, elliptical, pointed and flat. The veins are noticeable. The sturdy wood has been used for tool handles, golf club heads, knitting needles, mallet heads and cutting boards.

Why do urban gardeners like the dogwood tree and use it in their landscaping? In small city lots, it is a compact tree that grows up to about 30 to 40 feet high and approximately the same width. It doesn't take up too much gardening space. When in flower, the trees are covered with beautiful blooms. It combines nicely with azaleas and rhododendrons and other like-minded acid-loving shrubs that bloom at the same time in the spring. Bees and butterflies pollinate the flowers. As an understory tree in nature, it prefers some shade, and it appreciates good drainage. It is so well liked that several states, including North Carolina, Virginia, and Missouri have named the dogwood as their state tree or state flower.

What are the pitfalls of caring for a dogwood? Aside from anthracnose disease, aphids can attack the tree. Powdery mildew can also be a problem. The tree cannot stand to live in arid conditions, so watering is required in times of drought. The tree is a larval food for a number of caterpillars. Some people don't care to see caterpillars feeding on the leaves. In some city lots, the soil is compressed, and the tree has a hard time establishing itself. Lawn care people are careless about the actions of their weed whackers, and they cut or bruise the bark, thus disturbing the vascular system. Some dogwood trees attract a borer which can lead to the death of trees. A flower and leaf blight (fungus Botrytis cinerea) can also cause unattractive wrinkled patches on the flowers and loss of blooms. The fungus is not usually a problem in dry conditions, however, and it can be controlled by a fungicide. The biggest natural stressors are exceptionally cold winters, dry, hot summers, and wet weather.

When I recall how excited my mother was when she spotted a flowering dogwood in the wild, I wonder now why she never planted one. We lived on four acres of partially wooded land, and she could have had many. She would never have transplanted a wild-growing dogwood onto her property, as doing so might have brought in diseased samples.

I am looking forward to the spring to see how my dogwood returns to life from its winter dormancy. I'll know that the tender new leaves will suddenly appear as if overnight. It will flower in April or May (I'm guessing). I'll watch to see which insects come to pollinate it. In early summer, I'll hang a newer swing on a branch knowing that it can support the weight of my growing grandchildren. I'll watch for the drupes to appear in the fall. The leaves will start to turn red in September. Then I'll know to expect that after the first frost in October or November the leaves will drop exposing the dormant trunk and branches. The cycle will start anew.